History is written by the winners.

That’s the line that is most-frequently parroted when challenging the way we understand the world. The people who have gained the most power over the centuries are the ones who control the narrative of historical events, and the stories told about those events are told from the perspective of the ones who came out on top.

What is left unsaid by that axiom is that the history we have been taught isn’t just written by “the winners.” It’s written by white conquerers down through time. And it frequently neglects to take into account the accomplishments and the struggles of minorities. Their perspectives are almost always marginalized at best or downright ignored at worst. If we learn about these experiences at all, they’re often framed through the lens of a ghostwriter, applying a narrative that they believe would be more palatable to a wider (read: whiter) audience.

That also applies to the fictional history of the DC Comics universe. Created largely by white comic book writers, minority representation is few and far between. Yes, there are some prominent superheroes of color, but most all of the most recognizable comic book characters are white (or white-presenting).

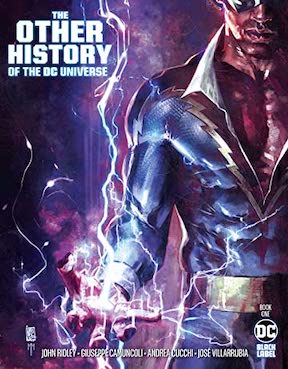

With the first issue of the new DC Black Label prestige miniseries, The Other History of the DC Universe, John Ridley is taking some of the historic moments in DC Comics’ (and the United States’) history and reworking them through the lens of some of those superheroes of color. The series was originally announced with the first batch of DC’s new BLACK LABEL books three years ago. After numerous delays and questions about whether it would even see the light of day, it’s finally ready to be read.

The first issue, which was released last week, focuses on Jefferson Pierce, also known as Black Lightning, in the years 1975-1995.

The first Black character to have his own DC Comics series, Black Lightning was created by writer Tony Isabella, who is white, and Guyanese-American artist Trevor Von Eeden, in 1977. The first series lasted 11 issues before falling victim to the DC Comics Implosion, which decimated the publisher’s line of books. Black Lightning has withstood the test of time, however, playing a prominent role in several DC Comics stories. Most recently, the character rejoined Batman as part of the Outsiders, in a comic written by Bryan Edward Hill.

In addition to being played by Sinbad in a famous SNL sketch spoofing the Death of Superman, Black Lightning now his own television series on the CW as part of the ARROWVERSE (although it was just announced that the show’s upcoming fourth season would be its last).

Under the pen of Ridley, Pierce brings an interesting perspective to the origins of the DC Universe. An Olympic gold medalist in the Decathlon, Jefferson Pierce’s powers began to manifest as he saw human rights violations happening during the Olympic games, but was unable to do anything. He became a teacher in Suicide Slum – the worst neighborhood in Metropolis – and became Black Lightning to make a difference in a place that was ignored by others in costumes.

Ridley focuses mostly on Jefferson Pierce the man, and how his upbringing and his day-to-day life affects his views on the world and the people around him. Pierce is driven and determined to improve the lives of his community, and it’s done to the detriment of his relationship with his wife, Lynn, and his two children. It’s heartbreaking to see a man who could have so much – a loving wife, two beautiful children and a successful career where he’s honored as a national Teacher of the Year – fall apart because of the metahuman abilities he only thought he wanted.

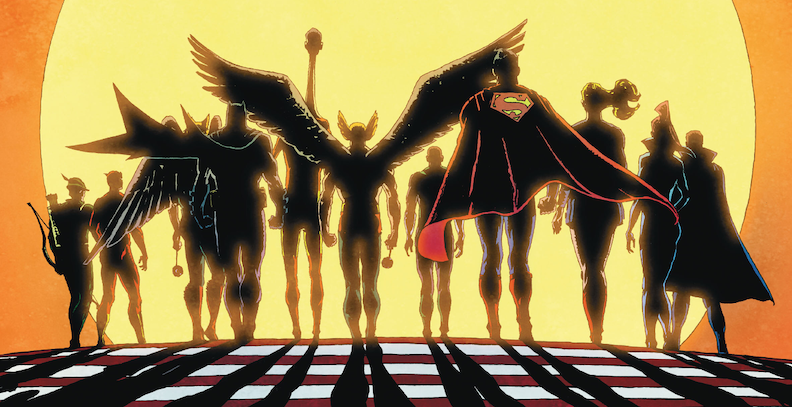

Pierce’s perspective on the other heroes isn’t exactly flattering, though the low opinion is probably earned. He chastises Superman for coming to Suicide Slum only to dress down Black Lightning for his tactics and turns down an invitation to the Justice League after they create fake villains as a “test” to see if Pierce is worthy of membership, even though Black Lightning had been fighting the good fight for a while already. He sees Superman (perhaps justifiably) as a symbol and savior of white America who does little for more marginalized people.

It’s not just white heroes who Black Lightning questions. When Mari McCabe – the hero who would become Vixen – comes to him for advice on being a hero, he tries to turn her away from the idea of looking for help from others, because they would never see her as one of them. And Pierce has complicated opinions on Green Lantern John Stewart – another Black American hero – because he sees Stewart as less-than-authentic and slightly aloof.

The one costumed hero who seems to get a pass from Black Lightning is Batman, who recruits Pierce for a mission overseas, admitting to Pierce that he’s calling on him not for his power set, but for the color of his skin. Batman eventually gives Pierce a new family, with the Outsiders, that opens Black Lightning up to new world views and opens him up to differing opinions.

Ridley eschews the typical comic book format of panel-by-panel dialogue for a prose approach. The words on the page are given life by the art of Giuseppe Canocoli, but the art is supplemental here, it’s the words that matter. The prose drives the story as opposed to a typical comic book where the art is the most important part. As such, the story is dense and certainly well worth the higher price tag.