Back in 1998, writer Warren Ellis began a short run on John Constantine: Hellblazer. But he cut his run short when DC Comics shelved a story he wrote about gun violence in schools, a story that wouldn’t be published for more than a decade, and one that is unfortunately still relevant today.

Watching the news of the horrific events at a school in Parkland, Florida Wednesday – the 18th shooting in just 45 days of 2018 – it’s inevitable for thoughts to turn to why someone would do such a thing. How could anyone work themselves up to bring a gun into a school and take their rage and their frustration out on young people whose lives have not yet really even started? What could motivate someone to snuff out the lives of their peers? It’s a horrific ordeal to even contemplate and I can’t bring myself to imagine what it must have been like for the kids who lived through it.

Watching the news of the horrific events at a school in Parkland, Florida Wednesday – the 18th shooting in just 45 days of 2018 – it’s inevitable for thoughts to turn to why someone would do such a thing. How could anyone work themselves up to bring a gun into a school and take their rage and their frustration out on young people whose lives have not yet really even started? What could motivate someone to snuff out the lives of their peers? It’s a horrific ordeal to even contemplate and I can’t bring myself to imagine what it must have been like for the kids who lived through it.

Unfortunately, there are now too many who know exactly what it’s like to live through something like this. School shootings are not a new phenomenon. The U.S. has experienced so many of these over the years, but the one that sticks out as the most prominent beginning to this awful era happened in April of 1999, when teens Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold walked into Columbine High School in Colorado and killed 13 people before killing themselves.

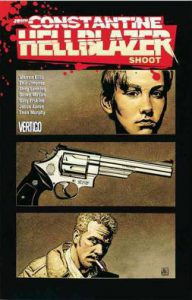

The Columbine killings, of course, had many far-reaching ramifications. One that many comic book fans of the time may remember involved Warren Ellis’ run on John Constantine: Hellblazer. Having taken over the book in 1998 with a six-issue story called “Haunted,” Ellis put a more political slant on the rogue mage. With his seventh issue, scheduled for Hellblazer 141, Ellis brought Constantine to the U.S., in an issue called “Shoot,” which dealt with a rash of incidents at schools where kids were shooting other kids.

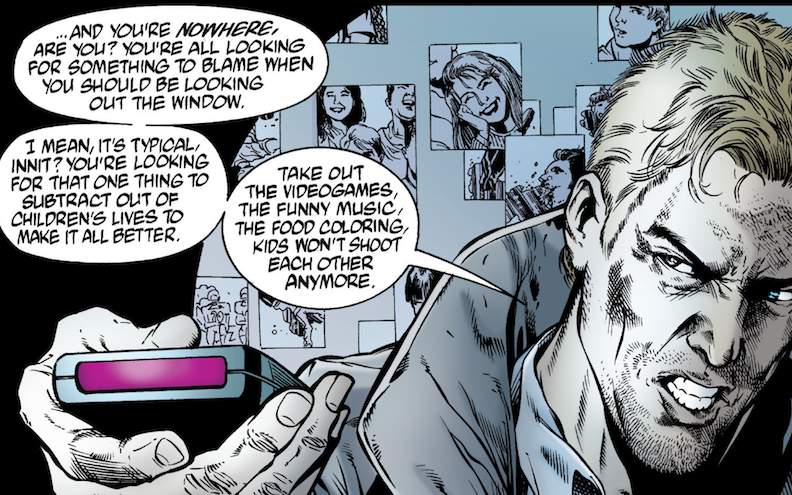

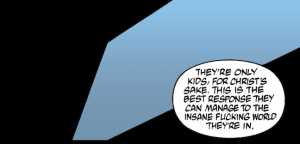

John, usually calm, cool and collected in the face of situations that could result in eternal damnation, loses his temper at a researcher looking into the shootings for a Senate subcommittee. Ellis pulls no punches in the story, using his main character to blame society and a culture of apathy that had no easy solution to stop them from killing each other.

Hellblazer 141 was scheduled for release soon after the killings at Columbine, and when then-DC Comics President and Publisher Paul Levitz learned about the contents of the issue, the story was shelved, and Ellis quit the book in protest. Even though DC Comics killed the issue, it wasn’t long before black-and-white copies of the comic began circulating. Originally, the PR department at the publisher was so excited by the prospect of the issue – before Columbine happened – that they had prepared review copies to send to the media to get some word of mouth going about “Shoot.”

I probably first read the story when those black and whites were posted online sometime in 2000 or 2001. The powerful subject matter and Ellis’ deft storytelling – along with pencils from artist Phil Jimenez – made the story something that people passed around, shared links to and printed out for themselves. Yes, the subject matter may have upset some, but it was probably something that could have sparked a necessary conversation about the nature of this violence and possibly some understanding among fans of comic books.

“Shoot” remained a story only seen through word-of-mouth and shared links online, or bootleg printouts passed around conventions for more than a decade. Everyone, including Ellis, had figured it would never see an official release. But then, in October 2010, a year after Levitz stepped down as publisher of DC Comics, the company reversed course. “Shoot” was published as part of a 96-page anthology called Vertigo Resurrected. It was later reprinted in a edition collecting that and five other Hellblazer stories from various writers and artists.

Having just re-read it earlier today, it still packs an emotional punch. After years of debate over whether violent video games or music or movies led to these tragedies, we’ve moved on to associating them with mental illness and other medical issues. But we still don’t know the true reasons of what would drive these people to become monsters who would waltz into a building filled with kids and teenagers and show such a wonton disregard for life. The most tragic part is how desensitized we’ve become to school shootings – because they’ve become such a common part of American life. Days after a shooting, we’re forced to move on because we know in the back of our heads that another one is coming.

We’re all just waiting for the next bullet to be fired. And we’re still nowhere.