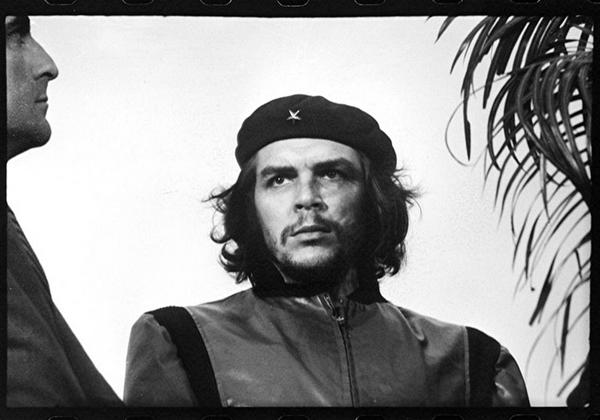

If you have ever attended college, or lived within fifty miles of one, chances are you have seen the image captured in this week’s header. To be certain, the image is one of the most well-known portraits in history, and has become as intrinsic a part of the college scene today as textbooks and alcohol.

One would be hard pressed to journey around a campus, any campus and not find at least one person with a flag, poster or t-shirt bearing his image. The reverence for the image of the man has stretched back a half-century, since his death in Bolivia in 1967. Yet while many can attest to having seen the famed Guerrillero Heroico image at some point in their lives, few seem to truly understand who the man behind the legend actually was.

To some, he is the embodiment of world revolution, and the great patron of the cause for social justice, the demise of class-based oppression and the beginning of the evolution of a ‘new man.’ Some view him as a symbol of challenging the Establishment and open rebellion. Others view him as a butcher, an evil and callous murderer who helped to engineer decades of brutality and oppression against the Cuban people. There are some who have no formal opinion on the man at all, and just wear his face on their clothing because they think it looks cool.

But to dismiss the man as a modern myth would be to greatly undermine his place in the history of the past century. Though he has been dead for almost fifty years, the legacy of the man behind the face is as diverse as his résumé. He was an intellectual, yet a pragmatist; an insurgent without formal training who became a keen military strategist. He was a physician who cared for the sick and infirm, and he was a guerrilla who held no reservations about killing the enemies of his movement. In many ways, as one of the most recognizable faces of the Cuban Revolution, he became a revolution unto himself. He was a poet-warrior, dogmatic, interspersing coldness with compassion.

Who is the man behind the myth?

Who is Che Guevara?

Today, we take a look at the legendary figure whose face has become an enduring sign of the times. Whether you come to view him as a hero, a villain, or even something in-between, no one will be able to deny the one concrete descriptor that applies universally to Che: he was unique.

Episode V: Only a Man, Part I

The Person: Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928-1967) | What He’s Known For: Fighting for World Revolution.

Though not especially wealthy, Che Guevara’s family would enjoy the trappings of a comfortable middle-class lifestyle in his native Rosario. When comparing his youth to that of another legendary 20th Century political figure (and revolutionary in his own way), certain parallels can be drawn between Guevara and Theodore Roosevelt: both men grew up with a profound desire to enact change upon the world, and both men battled chronic health problems which conflicted with their athletic, high-energy personalities. In the case of Che, he spent much of his youth reading poetry and philosophy, intermingling with athletes and intellectuals alike. He was very much the quintessential ‘Renaissance Man’.

As he grew older, Guevara made plans to attend university in Buenos Aires to study medicine, earning a degree in 1953. Yet it was a series of motorcycle trips during his education in the Argentine capital that truly set him down the path of becoming a revolutionary. Che’s first journey through rural Argentina in 1950 set the stage for his second, much more ambitious trek throughout South America in 1951. Though the ultimate purpose of the trip was to see Guevara and a friend arrive at the site of a Peruvian leper colony in the far north to provide volunteer medical care, the actual trip exposed Guevara to the cruel conditions many impoverished peoples across the continent faced. And for Che, there was a common thread that bound South Americans to their misery.

At this point, the Colloquium would like to add an addendum to this week’s piece, entitled Why the Cold War Sucked Ass, Part I. It will help piece together some of the dots in Che’s story.

So the Cold War sucked complete ass. In the simplest of terms, it was an ideological conflict between Capitalism (buoyed by the United States and its allies) and Communism (led by the Soviet Union and its allies). The key word here is “allies”: not only did the U.S. and Soviet governments maintain a broad spectrum of sociopolitical and military alliances, but they expected the rest of the world to support their side. This tended to suck for “the rest of the world,” because whichever side you ultimately came down on, the other side was bound to make life a living hell for you. Remaining neutral was rarely an option, because unless you were Austrians or Swiss (or so remote as to not really provide strategic value either way), one side or the other was likely to help topple your neutrality and replace you with friends sympathetic to their cause.

When studying the Cold War, this is why the actual “people are getting blown up and shot” wars tended to happen in areas that were (in that era) still developing: Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and most of Central and South America. The whole “blowing shit up” phase never really made it to American or Soviet shores, because the firecrackers the two sides had pointed at each other would have turned the planet into a glowing cinder in space a thousand times over. Whenever you watch a post-apocalyptic hellscape in movies from the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s, this is because people were living under the constant fear of being incinerated by a nuclear fireball at any moment.

Back to Central and South America: the Soviet Union saw this region of the world as an area rife for the expansion of their brand of Revolutionary Socialism, and sought to covertly assist various movements that brought about leftist governments there. The United States, which had been treating Central and South America as its own proverbial shopping mall in the grand tradition of nineteenth century imperialism for much of the preceding half-century, was less than thrilled by the prospect of seeing Soviet allies spring up points south of the Mexican border. And so, just as the Soviets intervened in various locales in the Eastern Hemisphere, the United States intervened in the Western Hemisphere. Strategically, both sides were trying to put the other in check in a persistent game of “let’s see how close we can come to global thermonuclear war”. But for many caught in the crosshairs of this ideological clash, the result was rampant poverty and abuse at the hands of corrupt puppet governments.

This was the South America that Che encountered on his 1951 trip: impoverished people living in squalor, while the wealthy elite lorded over them, backed in most instances by the economic and military might of the United States. As he endured scene after scene of economic hardship and suffering, Che became radicalized, seeing America and its capitalist imperialism as the root cause of suffering for South Americans. In an event that could adequately be described as “really poor timing for the West”, Che arrived in Guatemala in 1953, just in time to see its leftist government overthrown in a C.I.A.-backed coup d’état. Whereas Guevara had at one time planned to use his medical training to help the poor, this bitter slight against the Guatemalan people by the “American imperialists” would further push him to the edge.

Two years later, he had come to live in Mexico, the coup in Guatemala a festering wound. The mundane rationale behind the Americans’ intervention there — ostensibly to protect lands owned by the United Fruits Company (the company that would ultimately become Chiquita) under threat from Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz’s land reforms — infuriated Guevara. In reality, the Soviet Union was funneling weapons to the Árbenz Government through its client state Czechoslovakia (see above: the Cold War sucked), which allowed the seizure of United Fruits lands as an excuse to help topple the Árbenz Government. To Che, it was the final intolerable act of imperial aggression perpetrated by the U.S. in Central and South America. Continuing his study of Marxism in Mexico, Guevara would come into contact with a pair of brothers named Fidel and Raúl Castro, who were plotting to take the fight to the American-backed dictator of their native Cuba.

Then, all Hell broke loose.

Understanding “La Revolución”

Cuba, much like Guatemala and countless other locations around the world, had been caught up in the crossfire of the ideological battle of the Cold War. Here, the United States had propped up the immensely corrupt and unpopular General Fulgencio Batista’s military junta as a means of keeping its economic interests intact while preventing a leftist government from operating just ninety miles from Florida. Though originally something of a progressive in his own right, Batista had launched a coup to reclaim lost power in 1952. Spoiler alert: it did not go well for Cuba.

The Castro brothers, for their part, had attempted to launch the first revolution against Batista in 1953, an unsuccessful endeavor that got most of their partisans killed, and the brothers themselves arrested. Fortuitously for them, they spent only two years in jail before being released by Batista, who had enormous political pressure placed on him to extend leniency. Fidel and Raúl joined other Cubans in exile in Mexico, where in 1955 the two would meet Che. It was only through luck that Che was even around in Mexico to meet them: his exodus from Guatemala had nearly cost him his life when he attempted to join militia groups organizing to resist the new military junta there. Now, with the Castros and their band of exiles plotting a renewed offensive in Cuba, Che had his chance to put his revolutionary thought into practice.

The band called itself the 26th of July Movement, in honor of the first failed attempt at launching revolution in Cuba on (wait for it) July 26, 1953. The Castros, Guevara and their militia set sail from Mexico in 1956, intent on launching the overthrow of General Batista’s corrupt regime. Using a dilapidated yacht as their ferry, their landing did not quite go according to plan, and by that, the landing was attacked and almost destroyed from the word ‘go’. Only a quarter of the band landed by the 26th of July Movement survived to regroup in the mountains of Cuba to begin their campaign. During this time, as the legend goes, Guevara first picked up a weapon during the landing, when one of their comrades had taken to fleeing for his life.

Not coincidentally, this is the point where Che’s story begins to take divergent paths, depending on which Che you want to focus on. Though dealt a crushing blow upon landing in Cuba, the revolution managed to take hold in the Sierra Maestra Mountains. There, Che and his cohorts set to work improving the lives of the region’s impoverished farmers and peasants, helping to begin providing schooling and medical care to the population there. At the same time, Guevara began to exert ruthless control over the partisans under his command. In particular, while his actions were deemed later on by the Castro brothers as ‘heroic’, Che tolerated no dissent among the men he commanded, going so far as to beat and even execute them if they stepped out of line. Deserters were often executed under Che’s orders (and sometimes by his own hand) without trial. Most controversially, people deemed to be ‘traitors’ to the Revolution – spies or even Batista sympathizers – were executed by Che without trial, a personal policy that would continue long after the revolution had succeeded in seizing control of the country.

Both sides began upping the ante, committing atrocities against one another (and sometimes against their own people – War is Hell). But the ultimate fate of the Cuban Revolution was sealed in Batista’s relative incompetence, and the Cuban government’s inability to adapt to the guerrilla tactics being used principally by revolutionaries like Guevara. As Batista’s power faded, and the revolutionaries gained support, the Cuban government’s position became untenable. Che’s brilliant military strategy despite being heavily outnumbered and at constant peril of destruction has posthumously won him praise even from American military leaders. The revolutionaries seized Santa Clara in late-December 1958. On January 1, 1959, Batista fled Cuba; Guevara would beat Fidel Castro into Havana by almost a week.

Many people assume that the revolutionary forces under the Castros and Guevara immediately set to work transforming Cuba into a communist state upon their victory in 1959. In reality, Guevara was the instrumental force in pushing Cuba into communism; Fidel Castro was more circumspect, and cautious of bringing U.S. intervention against their new government. Guevara would serve in a number of roles for the brand-new government, including overseeing the trial and execution of hundreds of enemies from the old Batista regime. Later on, he would head up the country’s economic development when the United States began its policy of clamping down on the increasingly-Socialist state by limiting trade.

Though he would be successful in negotiating economic deals with the Soviet Union and its allies, his quota system has been retroactively proven to be a major failure, which helped to increase the hardships for many Cuban laborers. At the same time, his push to improve literacy rates and reduce social inequality in Cuban society were hailed as major triumphs. Guevara would ultimately travel around the world as an emissary of the revolutionary government, including a much-publicized trip to the United States to speak at the UN in 1964. Some historians believe that it was Guevara who helped convince the Soviet Government to bring nuclear missiles to Cuba as a means of protecting it from continued attacks by anti-Communist forces. By 1962, Cuba had already repelled the Bay of Pigs Invasion orchestrated by the C.I.A., and had seen a probable terrorist attack allegedly sponsored (if not outright conducted by) the U.S. Government in Havana Harbor in 1960. It was during the memorial service for the victims of the blast that the Guerrillero Heroico portrait was snapped.

Through diplomatic channels Guevara had helped to forge, the Cuban Missile Crisis became sort-of a big deal in 1962, when the planetary pissing contest almost erupted total war. Thankfully, the world survived going down the road foretold in Planet of the Apes, and would never again come that close to seeing a nuclear holocaust. Except for 1983, when it almost happened again. And in 1995, which was absolutely hilarious because the Cold War was supposed to be over with at that point.

And on that note, we shall leave it here for the week.

~

This Week in History at the Colloquium

On June 19th, 1986, veteran NBA journeyman Marvin Williams was born; University of Maryland star and Boston Celtic draft pick Len Bias died of a cocaine overdose before ever playing a professional game.

On June 20th, 1837, Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent ascends to the British throne and becomes Queen Victoria, the second-longest serving monarch in the country’s history, behind only Elizabeth II.

On June 21st, 1945, the Battle of Okinawa ends in U.S. victory over the forces of Imperial Japan after nearly three months of bloody fighting.

On June 22nd, 1990, Checkpoint Charlie, the infamous border crossing between East and West Berlin (and future Colloquium subject!) is dismantled, removing a former potential flashpoint of the Cold War.

On June 23rd, 1865, Cherokee-born Confederate General Stand Watie surrenders one of the last rebel armies in the American Civil War in Oklahoma.

On June 24th, 217 BC, the Carthaginian general Hannibal defeats the Romans at the Battle of Lake Trasimene during the Second Punic War.

On June 25th, 1950, forces of the Democratic People’s Republic of (North) Korea launch an invasion of the Republic of (South) Korea, precipitating the beginning of the Korean War – a war that is technically ongoing to this day.

~

We hope you enjoyed Part I of our special two-week series on Che Guevara. Next week, the Colloquium will conclude its look at the Argentinian revolutionary by looking at his exploits in Africa and South America following his departure from Cuba, along with the commercialization of a portrait that has become famous the world over as the token symbol of leftists, revolutionaries and hipsters alike. As always, if you have comments or questions about this week’s episode, feel free to follow me and hit me up on Twitter, @biffkensington. Be sure to support the Geekery by checking out all of the amazing content produced by our staff, and we will see you back here next week for another exciting installment of the Colloquium! Have a great week everyone, and take care!