It has been quite a week for the world’s most famous mountain.

In what will assuredly go down as one of the strangest events in the history of Mount Everest, four climbers were allegedly found dead in a tent perched high up on the South Col of Mount Everest due to unknown causes. The discovery, which has since been disputed by government officials in nearby Kathmandu, caps a tumultuous week for the region following the news that the famed Hillary Step — a famous geologic feature on the south side of the mountain — had possibly collapsed. Whether the four bodies alleged to have been found by climbing Sherpas exist or not, the death toll has been steep on the mountain so far in the 2017 season, with six recorded deaths thus far.

Climbing fatalities are nothing new for the world’s tallest mountain; hundreds of mountaineers arrive in the Himalayas each year to strive for the roof the world, standing at the summit of the highest mountain on Earth. Each new climbing season brings brave souls who risk their lives to achieve this incredible feat; some make it, some turn back before reaching the top, and some never come off the mountain. Such is the allure of conquering the mountain that some once thought impossible to conquer. People willingly spend tens of thousands of dollars to trek in a place where dead bodies are left frozen in time, serving as much as a reminder of the price climbers may pay as they are geographic markers on the way to the top.

The mountain has been a mystifying force in the consciousness of adventurers and explorers since its first real surveying in 1856. Officially named Mount Everest in 1865 by the Royal Geographical Society of Britain (the peak is also known by its Nepalese name Sagarmāthā and by the Chinese as Chomolungma), the mountain has played host to a number of major expeditions and conquests over the last century. Despite political instability and its utter remoteness making access to Everest difficult, individuals from the earliest expeditions on dreamed of standing on the top of the world. Over the years, various men and women have left an indelible impression on the culture and history surrounding the mountain — names that are now famous to the mountaineers who dare to climb there.

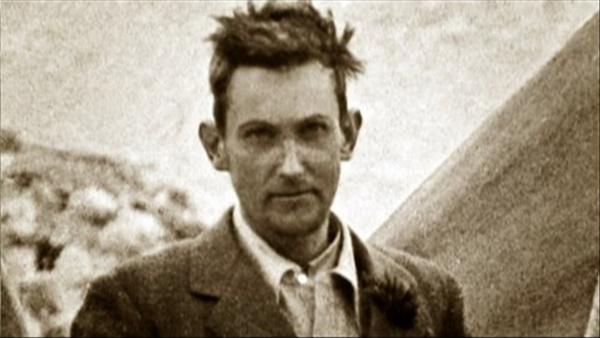

For many, however, one name resonates more poignantly than all the rest. A veteran of the Great War and an adventurer at heart, he climbed into a frozen hellscape with one goal in mind: going where no man had ever dared go before. The Casual Geekery is proud to bring you the second episode of The Colloquium, looking at the exploits of legendary mountaineer George Mallory.

Prepare yourselves for badassery.

Episode II: “Because It’s There”

The Person: George Mallory (1886 – 1924) | What He’s Known For: Climbing Everest

Though the first recorded sighting of the peak was made in the early eighteenth century, it would take until 1921 before the first serious attempts at scaling Mount Everest would be made. The mountain straddles the border between Nepal in the south and Tibet, a contested region of China, to the north. Owing to its position on the border, and the delicate political and religious issues which have engulfed this region of the world, access up until the 1920s to Everest was tightly controlled by local officials. In fact, before the 1921 expedition, the only way to get remotely close to Everest was for the British to launch a clandestine military expedition through Tibet. Because when it comes to planting your proverbial flag on the roof of the world, silly things like international borders matter not when you can send in a figurative spy team.

Though the Nepalese route to Everest remained sealed to outsiders for some time, Tibetan officials finally authorized an official entry for explorers to try and climb the mountain in 1921. One must remember, this period of time in the immediate aftermath of World War I was coming on the heels of the closure of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, where legendary explorers like Shackleton and Scott had become adventurers of international renown for their treks through Antarctica. With the southern pole now open, and the conquest to the bottom of the world now closed, it seemed to many as though the last great challenge would be reaching the top of the world.

Enter George Mallory.

The son of a clergyman and a clergyman’s daughter from Cheshire in England, George Mallory was a gifted academic and prodigious climber, having managed to summit famed Mont Blanc in 1911, some ten years before his first journey to Tibet and the mountain that would come to consume his dreams. As with most young men of the period, Mallory would leave his position as a teacher to fight in the First World War, returning several years later with an intense desire to accomplish more with his life. From his early days in schooling, the young Mallory had been fascinated with mountain climbing. And with the news that the British government was arranging for a special survey team to Everest at the invitation of Tibetan officials in 1921, the time seemed right to take a proverbial leap of faith.

Leaving behind a wife and three children, Mallory volunteered for the 1921 expedition to Everest, which was as much about scouting potential routes up Mount Everest as it was doing actual climbing. It was during this trip that Mallory and the rest of the expedition located a path up the mountain at the East Rongbuk Glacier, which is still the main route used by climbers attacking the mountain from the north face to this day. The team manage to make it to the ridge atop East Rongbuk called the North Col (Altitude: 23,031 Feet), where nearly vertical ice walls require strenuous efforts to traverse. Several thousand feet above them loomed the summit as they retreated, having “prepared the ground” for a future attempt.

That attempt would come in 1922, when the second British expedition to Everest sought to advance beyond the North Col towards the summit. Three serious attempts were made during the 1922 expedition, with George Mallory back again to try and tame the mountain. At first, Mallory and his climbing partners attempted the climb without supplemental oxygen, but after witnessing the speed at which their teammates moved using oxygen canisters, all subsequent attempts were made with supplemental oxygen.

The third and final attempt on the mountain in 1922 would exact a steep price on the team. Despite having reached a then-record altitude of well over 27,000 feet, seven Sherpas on the expedition would be killed in an avalanche on their final descent from Everest. Their deaths, the first known victims of the mountain, was an ominous sign to those who dared risk going for the summit, and sparked a great deal controversy around continuing to attempt to conquer the mountain. Upon his return to England, Mallory was questioned as to why he would even want to attempt such a dangerous endeavor. His response has become legendary to mountaineers, and particularly those who seek to climb Everest: “Because it’s there.”

Finally, in 1924, the British government sent its third major expedition to Everest. And once more, George Mallory would leave his family and career behind in an effort to be the first person to stand on the summit. Arriving in June to the mountain that had come to haunt his dreams, Mallory and the other members of their team set about the arduous task of preparing to tackle the mountain. On June 8th, Mallory and his climbing partner Andrew “Sandy” Irvine set out high on the northeast ridge of the mountain, and were tracked for a time by fellow climber Noel Odell, several thousand feet below. The two men were less than a thousand feet from the top of the world when a rolling cloud bank obscured them from view.

It was the last time Mallory would be seen for seventy-five years.

The 1924 Expedition: Into the Death Zone

The 1924 attempt on Everest was the third major expedition to attempt to climb to the top of Everest along the northeast ridge route, now known as one of the most difficult and dangerous climbs in the world. The entire process of climbing at altitudes so high requires immense preparation, with climbers needing considerable time just to acclimate themselves to the altitude. Even today, ailments such as altitude sickness and edema can be considered life-threatening as low on the mountain as the East Rongbuk Glacier and the North Col. Just getting to the North Col itself requires traversing over deep chasms in the glacier and steep cliffs. Making it past the North Col brings more arduous climbing, with the steep ascent a serious fall hazard for climbers not using fixed ropes — a luxury neither Mallory nor Irvine had in 1924. The extreme cold and elements make frostbite and hypothermia a very real threat, and many climbers even today suffer through the loss of fingers, toes, and sometimes worse due to the elements. One particularly gruesome accident in 1996 led to the loss of a nose due to frostbite.

From here, things get really bad.

Progressing above 8,000 meters (or roughly 26,000 feet) brings mountain climbers into a region known as the “Death Zone”. At this altitude, the air pressure is so low that the human body is incapable of acclimatizing to the thinness of the air. Climbing at an altitude where most commercial jets cruise at, the body literally begins to break down. Food cannot be digested at this level, and the loss of oxygen results in a deterioration of brain function and strength. Quite literally, entering the death zone without supplemental oxygen is a severe risk, for the body begins to die at this level. On Everest, climbers must endure 3,000 feet of climbing in the Death Zone to make it to the top. At this altitude, the physical strain on the human body is so great that any attempt at a rescue is practically impossible.

If you die here, your body becomes a permanent fixture of the mountain.

Upon entering the Death Zone, climbers will begin traversing the Northeast Ridge, coming to a series of rock faces known as the Three Steps. It was here that Mallory and Irvine were last seen by Noel Odell. It is also here where the great controversy exists: because they were last spotted on the Steps, it is unclear how far up the mountain the two actually made it. By June 9th, the two men had vanished, and were presumed to have been lost on the mountain. All efforts to track them down failed, and they were officially presumed dead pending the expedition’s departure from the mountain. The mystery of Mallory and Irvine’s disappearance would linger for decades, with people wondering whether the two had managed to make it to the summit — getting over the Steps is the last technical obstacle on a northern assault on Everest. It is likely that, had Mallory made it past the Steps, that he would have been able to reach the top.

In 1999, on an expedition specifically designed to look for answers regarding the disappearance of Mallory, mountaineer Conrad Anker happened by chance to locate the body of a long-deceased climber, wearing clothing appropriate for the era in which Mallory and Irvine were lost (on Everest, the cold, thin air helps to preserve the bodies that are entombed there). At first, Anker believed he had stumbled across the body of Sandy Irvine, owing to its location near the site where Irvine’s ice ax had been recovered in 1933. An inspection of the clothing however revealed the frozen corpse to be that of George Mallory. His remains had spent seventy-five years on the north face of Everest before being located.

It was from this discovery that Mallory and Irvine’s final hours could be pieced together. An inspection of Mallory’s body revealed a rope-jerk injury around his abdomen, proving that Mallory and Irvine had tethered to one another with a rope, and that one of the two men had slipped. Mallory wound up falling down the mountain, though it was not a free-fall: a significant wound in the corpse’s forehead was inflicted by Mallory’s ice ax, indicating that he had attempted to slow his rate of fall, with the ax ricocheting off a rock and striking him in the skull. Coming to rest more than a thousand feet into the Death Zone, Mallory attempted to cross his legs to ease the discomfort of a compound fracture suffered from the fall. It is likely that he passed out from the pain of his multiple injuries in that position, finally succumbing to the extreme cold and altitude several hours later.

Mallory’s remains were properly buried on the side of Everest using a rock cairn, his effects catalogued. Notably, one important piece of evidence was located, while two others were missing: due to the risk of snow blindness on the mountain, climbers have to wear special snow goggles to protect their eyes. Mallory’s goggles were found in his clothing, suggesting that he and Irvine had begun the climb down Everest in the darkness. More noteworthy was the missing camera the two had taken to document a successful summit bid, along with the picture of Mallory’s wife Ruth that he had promised to leave on summit were he to make it there. Because of the remarkable preservation of other objects on Mallory’s corpse, the absence of this photograph is highly conspicuous. As of 2017 though, no evidence has emerged which definitively proves whether or not Mallory made it to the top of Everest.

The Aftermath: Knocking the Bastard Off

Upon the expedition’s return home, George Mallory and Sandy Irvine were mourned as heroes who had fallen in service to their country. The loss of Mallory in particular led to a sort-of mythologization, romanticizing his courage and spirit in the face of such daunting odds. His death made headlines all over the world, including a small town in New Zealand called Tuakau. Here, a five-year-old boy named Edmund Hillary would learn of the heroic attempt to conquer Mount Everest, leading him one day to pursue the dream that had claimed Mallory’s life. In 1953, traveling up the south face of the mountain, Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay would finally reach the summit. He would spend much of the rest of his life devoted to philanthropic efforts, helping the Sherpa people of the region receive much-needed assistance.

In many respects, Mallory could be seen as one of the last great explorers, though this would be a gross-simplification of the man and his legacy. Arguably, no one figure had a greater impact on the history of Everest than Mallory, whose death made the conquering of Everest a point of honor that must be achieved, risks be damned. Through Mallory’s death, an entire generation of mountaineers were compelled to push the limits of human endurance, including Hillary. The exploits of these individuals would help create the modern mountaineering industry and open up a whole new frontier for people to explore. Even relatively-inexperienced climbers can now (at considerable risk) travel the same route Mallory and Irvine took towards the summit.

At its core though, the story of George Mallory and his dream of conquering Everest represent a fundamental virtue that all persons of great character strive to achieve: determination. He could have led a quiet, simple existence as a teacher, safe with the comforts and modern conveniences of home, but the challenge of doing the impossible was too great to pass up. The risk of climbing so high, in conditions that would make a polar bear shiver were hellish and brutal, and Mallory was well-aware that he could be climbing to his death on his final ascent. Despite the danger, Mallory went on, because the fear of death cannot overcome immeasurable courage. George Mallory is, in many ways, a symbol of honor and fearlessness that should be remembered by the generations to come.

After all, the man faced a challenge head-on where sub-zero temperatures, hurricane force winds, air that is too thin to breathe, the risk of falling for miles onto rocky outcroppings and your own body consuming itself were just some of the dangers… Then he decided to take the challenge three more times. Just walking around with balls the size of Volkswagens is tough enough; imagine hauling them straight up over 28,000 feet. That is George Mallory.

~

We hope you enjoyed this week’s episode featuring the exploits of a mountaineering legend. Next week, we will warm things up considerably as our focus shifts to the desert, and a group of men so awesome, they put Sin City on the map. As always, if you have any questions or possible suggestions for future episodes, feel free to hit me up on Twitter @biffkensington. Take care folks, and enjoy your holiday weekend.